If Congress wants to write laws that effectively regulate companies like Facebook, Google and Twitter, it needs to change the ways it interacts with those companies, because these hearings ain’t it. They’re a waste of everyone’s time, and no one is even pretending otherwise. To truly put Big Tech on the spot, future hearings need to do — at the very least — these three things.

Change the format

Five minutes of free-form questioning by 60 or 70 representatives sequentially is the current format for House hearings, and it’s a disaster — especially on Zoom or Bluejeans or whatever Congress uses.

Over and over again we get representatives who spend three-fourths of their time on de facto opening statements that are as likely as not to be pandering bloviations redundant with what’s already been said. Once that’s finished, the short remaining time forces them to require yes or no answers to poorly posed questions about complex topics.

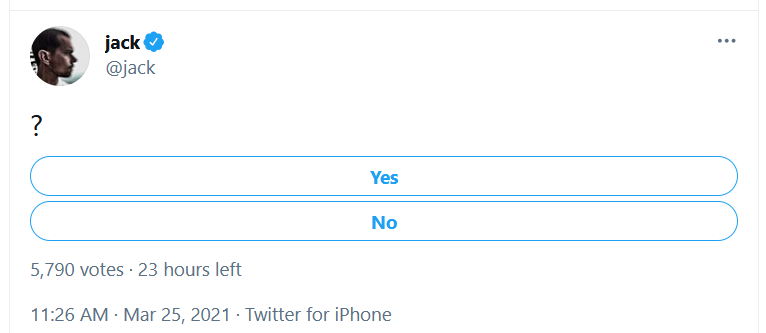

Because there’s nothing compelling these CEOs to actually respond with yes or no, they always, always respond with a longer answer. Have done for years, yet representatives still complain about it, even when their questions can’t conceivably be answered with a yes or no without over-committing or self-incrimination.

Because there’s nothing compelling these CEOs to actually respond with yes or no, they always, always respond with a longer answer. Have done for years, yet representatives still complain about it, even when their questions can’t conceivably be answered with a yes or no without over-committing or self-incrimination.

When you ask, and this was an actual question, “Do you think the law should allow you to be the arbiters of truth, as they have under section 230?” — you cannot seriously expect a yes or no answer. It’s the tech equivalent of “Have you stopped beating your dog?”

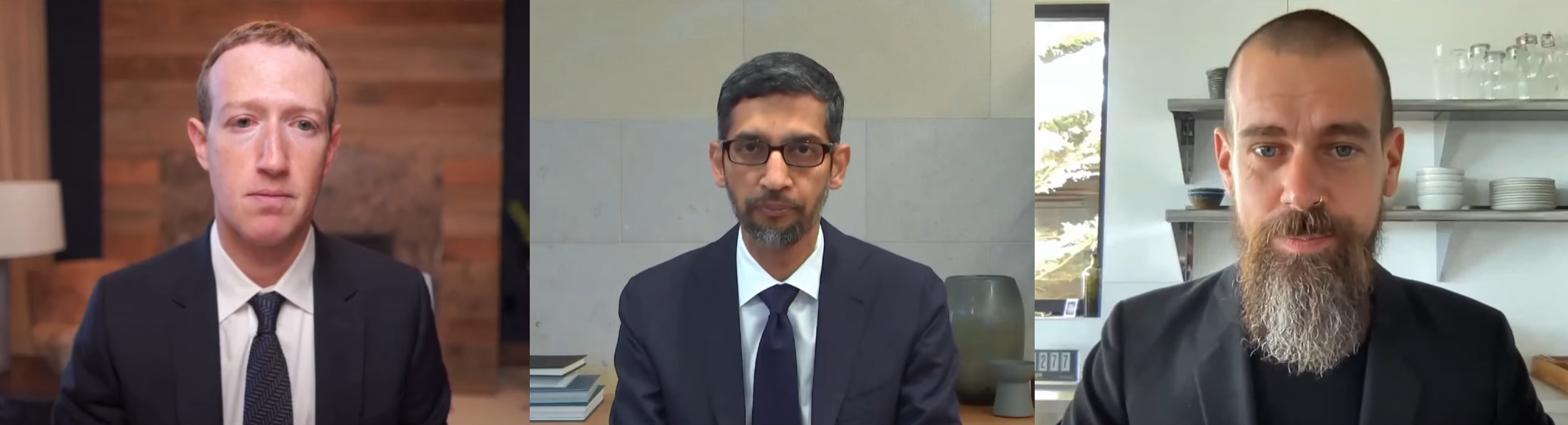

Faced with pointless or impossible questions, Zuckerberg maintained a sort of perpetually aggrieved countenance, looking more like the dog than the beater. Pichai tuned out, missing questions or offering obvious platitudes when called on. Dorsey, plainly bored, tweeted his way through the hearing and answered in monosyllables even when it was not required of him.

As irritating as this political theater is to watch, it must surely be more so to take part in. Seeing that nothing worthwhile can be said or done in these five-minute abuse sessions, the highly visible chief goal of the CEOs is to run out the clock — safe and incredibly easy to do. Sometimes they appeared to be barely paying attention, secure in the knowledge that they can respond “these are nuanced issues… we take this very seriously, Congresswo—” before being cut off. Begging off based on being “unsure about the exact details” and saying you’ll follow up is another zero-commitment option.

As irritating as this political theater is to watch, it must surely be more so to take part in. Seeing that nothing worthwhile can be said or done in these five-minute abuse sessions, the highly visible chief goal of the CEOs is to run out the clock — safe and incredibly easy to do. Sometimes they appeared to be barely paying attention, secure in the knowledge that they can respond “these are nuanced issues… we take this very seriously, Congresswo—” before being cut off. Begging off based on being “unsure about the exact details” and saying you’ll follow up is another zero-commitment option.

The format needs to be changed to allow for substantive discussion, firstly by extending each member’s questioning time limit to eight or 10 minutes at least; secondly, by providing some kind of guideline for answering, for instance guaranteeing 10 seconds but silencing them after 30. So much is lost to crosstalk in these video hearings that ultimately it’s better to allow a bad answer to go for 20 seconds than to object to it for 25.

It may also pay to limit the participants, allowing the leaders of the Committee to allocate time as they see fit to a smaller number of representatives who have more than boilerplate outrage to put on the record. How exactly this could be accomplished is probably subject to a raft of rules and procedural things, but seriously, there’s no point in having most of these people involved. Keep it fair, keep it bipartisan and let each party either exclude its cranks or own them.

Real consequences or legally extracted promises need to exist as well. One questioner brought up an independent audit Jack Dorsey promised — on the record, to Congress — in 2018. It never took place, with Dorsey saying they decided to do something else instead. So it wasn’t a promise, it wasn’t a requirement and there was no legal compulsion to do anything at all. Why even bother asking if all you’re doing is asking for a favor? Lawmakers need bite to back up their bark, and if that doesn’t exist, they should refrain from barking so much.

Have a real agenda

If the format changes, the agenda needs to as well. Because if we simply allow these clueless lawmakers more time to read their scripts, the scripts will, like legislative goldfish, expand to fill the time allotted to them.

We’ve seen hearings that have made a difference, usually because the people involved have evidence to present and arguments to accompany it. Vice President Kamala Harris was great at this, having a background as a prosecutor — she made it pretty hot for Zuckerberg back in 2018. Reps. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) and David Cicilline (D-RI) made Jeff Bezos look like he was either ignorant or had something to hide last year by confronting him with incriminating testimony and requiring a real answer.

Unfortunately, we can’t trust our legislators to be informed (or truthful) on these issues or really to even care. Most of the time their questions come off like something anyone could throw together an hour before the hearing with some quick background searches. Some of it (like hammering on the long-settled NY Post/Hunter Biden debacle) is so out of date that it proves beyond a doubt that the questioner had no intention of addressing the issues ostensibly at hand. Why let them waste everyone’s time on irrelevant topics?

Subpoena power comes with its own problems — no one wants to fight a court battle every time they want to ask a few questions — but if Congress is not going to use the tools available to it in the pursuit of legislating these issues, what exactly do they bring to the table?

If hearings don’t have a driving force behind them, such as an event, investigation or document release, they are almost by definition just a way for representatives to generate sound bites and appear concerned to their constituency. Today’s event is very much an example of this.

Bring in principals, not figureheads

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg listens during a joint hearing of the Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee and Senate Judiciary Committee on Capitol Hill April 10, 2018 in Washington, DC. Facebook chief Mark Zuckerberg took personal responsibility Tuesday for the leak of data on tens of millions of its users, while warning of an “arms race” against Russian disinformation during a high stakes face-to-face with US lawmakers. (Photo: BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP/Getty Images)

Mark Zuckerberg, Sundar Pichai and Jack Dorsey are very smart. Very well-informed. Very important. But their roles as figureheads as well as decisionmakers in their companies and industries makes it nearly impossible for them to say anything that hasn’t been drafted and cleared ahead of time, and they are also free to not remember or defer to an absent colleague.

There’s no blood to squeeze from these stones, so invite someone else. This was a hearing about disinformation — these companies have people making everyday decisions and directly overseeing projects on that topic. They should be the ones being asked to answer Congress’s questions.

It’s conceivable, if almost certainly untrue, that Zuckerberg “doesn’t recall” conversations about hiding abuse of Facebook data from users. Getting him to take that position is a victory of a sort, but it would be better to have the person whose responsibility this actually was, someone who can’t take refuge in hysterical ignorance.

Certainly these VPs and heads of what have you would also be media trained and prepped with canned statements, but it’s better than the alternative. These CEOs are Teflon-coated and this isn’t their first time in front of the shouting squad. They no longer care about anything but keeping the hearings as boring as possible and avoiding a news cycle. (Dorsey’s weird clock was a great blow-off valve for this. Pichai’s aggressively ordinary background gave you nothing to focus on but his answers — wrong play. And Zuckerberg’s high-quality camera setup only made him look more damp and robotic.)

Every time one of these hearings takes place, the overwhelming impression one gets from them is of a lost opportunity. Here are elected lawmakers given a chance to speak directly to some of the most powerful people in the tech industry, and perhaps nine out of 10 use that time to retread old topics, thrust dubious information into the record, or simply relish their chance to push around someone like Mark Zuckerberg. The temptation is understandable but legislators must put the country first.

Though some representatives raised important issues today, the format prevented them from extracting substantive answers; the lack of a cohesive agenda or central documents meant they had no compelling evidence to put forth; the subjects of their questioning were bored and had no reason to say anything beyond what they put in their carefully prepared opening statements. If future hearings — concerning this or other industries — don’t change things up, no one should be surprised if they, like this one, yield nothing but hot air.