While the old adage goes, “Find a job you love doing, you’ll never work a day in your life,” it’s safe to assume this was well before the age of the YouTuber, “plandids” and the stock market of things. StockX may be a multibillion dollar juggernaut with massive influence radiating throughout sneaker culture today, but it started with taking the leap to transforming a personal passion into a business plan.

For founder Josh Luber, keeping his love for sneakers separate from his career was very intentional at first. As he continued to invest into his hobby, he saw something from his corporate jobs that was altogether missing from sneakers — data. As he established and dove deeper into the numbers, an entirely different vision arose. A basketball game, a check and a business later, StockX was born.

What began as a basic price chart of online sales that screamed more Microsoft Excel than startup unicorn has now become one of the most intriguing marketplaces in the world.

The timing was remarkably fortuitous. Sneakers crescendoed from a rising niche to a frenzy over the past decade, and the demand for authenticated goods likewise soared. Few other companies put together the core mechanisms required for a market to function effectively for this category. What began as a basic price chart of online sales that screamed more Microsoft Excel than startup unicorn has now become one of the most intriguing marketplaces in the world.

What’s a sneaker worth?

Before co-founding StockX, Josh Luber was consulting at IBM, deliberately working outside of sneakers to maintain it strictly as a hobby. That setup continued until he realized the opportunity to organize data around his beloved collection.

Markets can’t exist without prices, and the price of a sneaker in the secondary market a decade ago was difficult to discern. There was, of course, the retail price, but popular sneakers often gained value over time based on demand, which could wildly fluctuate over time. By scraping data openly available on eBay for over 13 million transactions, Luber and a team of 17 volunteers established Campless, a constantly updated sneaker secondary market pricing guide that launched in 2012.

“While it had a lot of flaws in it and required a lot of manual work, it gave probably the best reference point at the time,” COO and co-founder of StockX Greg Schwartz says. The Campless team was simply pulling prices from closed eBay auctions and analyzing trends from there, much like any individual seller would probably do before posting their own shoes. By scaling up the size of the dataset though, they were getting much more accurate market-clearing prices than were previously available for both buyers and sellers.

Similar to the auto industry’s Kelley Blue Book that offers estimated values for cars by model and year, Campless offered in-depth numbers on the secondary sneaker market that would eventually become a tentpole and proprietary offering of StockX.

Helicopters over malls and the chaotic rise of the sneaker craze

When Luber and his team launched Campless, there weren’t easily accessible options for buying sneakers in limited releases. Enthusiasts could buy directly from the retailer by lining up and camping out for in-store drops, scour eBay for the most legit-looking seller with the best price, or have a plug or backdoor avenue to get their prized pairs. All three options were fraught.

Josh Luber at TechCrunch Disrupt NY 2017.

Campless’ name and “know more, camp less” tagline referred to consumers camping out — sometimes spending days in line — for the latest, most coveted sneaker releases. Flight Club, which opened in New York City in 2005, was initially for consignment and typically carried rare, older shoes rather than new pairs. For individual resellers though, eBay and Craigslist were the only options to set up a one-on-one transaction at their own discretion, and neither platform had the necessary safeguards for sneaker authentication or price regulation.

This fractured system might have been sufficient for a market that remained a relatively small niche. But it had been steadily growing in popularity since the 1980s, and the scale got even bigger in the 2010s.

In a 2014 interview with eBay, Luber shared the significance of this period, pointing to one shoe as causing a sea change in the popularity of the category: the February 2012 NBA All-Star Weekend release of Nike’s “Galaxy” Foamposite, part of a celestial-themed pack worn by basketball greats like LeBron James, Penny Hardaway, Amar’e Stoudemire and Kevin Durant.

Trusted sneaker blog Sole Collector called this specific release “one of the most chaotic sneaker releases of the last decade” because it caused “riots nationwide as sneakerheads tried desperately to get their hands on pairs.”

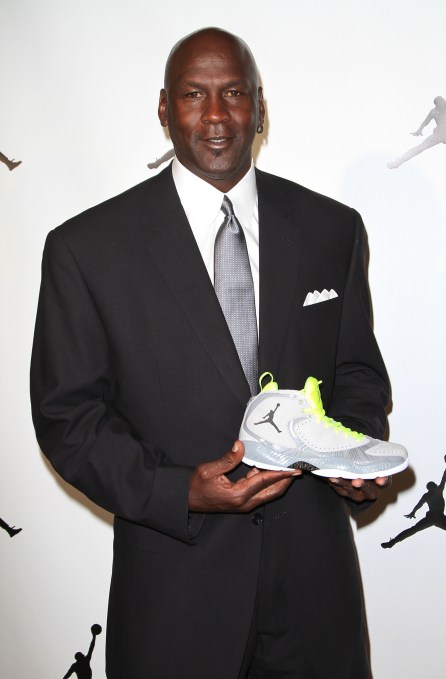

Michael Jordan attends Jordan All-Star With Fabolous 23 in 2012. Image Credits: Nike (Alexander Tamargo/WireImage)

“That was definitely the first time I remembered people other than my group of friends that loved shoes talking about a ‘drop,’” 24-year-old sneaker enthusiast Mark Sabino said.

Andy Oliver, director of e-commerce at the sneaker and streetwear lifestyle brand Kith, looks back on it as a tipping point as well. “I think it was a combination of the right model — Foams were super hot — with a graphics treatment that was really unique at the time. Then, from a marketing perspective, it’s tied to All-Star Weekend, which was a huge deal in 2012. When everyone started to get a sense that they were mostly unattainable, they blew up on another level.”

Brendan Dunne, co-host of Complex Media’s sneaker show Full Size Run, said the release set a new benchmark for chaos and hype. “I think the image of helicopters flying over the mall in Orlando where they released is the enduring image.”

A community that had been around since the 1980s was hurtled into the mainstream eye. Yet even more fuel was added to what Luber called “limited edition sneaker collecting” with the growing popularity of Instagram. For the first time, sneaker enthusiasts could share their favorites with the entire world, showing off their rare finds to potentially millions of people on their feeds and not just their friends in person. Securing that All-Star Weekend drop meant not just being cool, but globally cool, intensifying the pressure on a market that was completely unprepared for the scale of demand that was arriving.