The pandemic upended the way people shop for their everyday needs, including groceries. Online grocery sales in the U.S. are expected to reach 21.5% of the total grocery sales by 2025, after leaping from 3.4% pre-pandemic to 10.2% as of 2020. One business riding this wave is Mercato, an online grocery platform that helps smaller grocers and specialty food stores get online quickly. After helping grow its merchant sales by 1,300% in 2020, Mercato has now closed on $26 million in Series A funding, the company tells TechCrunch.

The round was led by Velvet Sea Ventures with participation from Team Europe, the investing arm of Lukasz Gadowski, co-founder of Delivery Hero. Seed investors Greycroft and Loeb.nyc also returned for the new round; Gadowski and Mike Lazerow of Velvet Sea Ventures have also now joined Mercato’s board.

Mercato itself was founded in 2015 by Bobby Brannigan, who had grown up helping at his family’s grocery store in Brooklyn. But instead of taking over the business, as his Dad had hoped, Brannigan left for college and eventually went on to bootstrap a college textbook marketplace, Valore Books, to $100 million in sales. After selling the business, he returned his focus to the family’s store and found that everything was still operating the way it had been decades ago.

Image Credits: Bobby Brannigan of Mercato

“He had a very basic website, no e-commerce, no social media and no point-of-sale system,” explains Brannigan. “I said, ‘I’m going to build what you need.’ This was my opportunity to help my dad in an area that I knew about,” he adds.

Brannigan recruited some engineers from his last company to help him build the software systems to modernize his dad’s store, including Mercato’s co-founders Dave Bateman, Michael Mason and Matthew Alarie. But the team soon realized it could do more than help just Brannigan’s dad — they could also help the 40,000 independent grocery stores just like him better compete with the Amazon’s of the world.

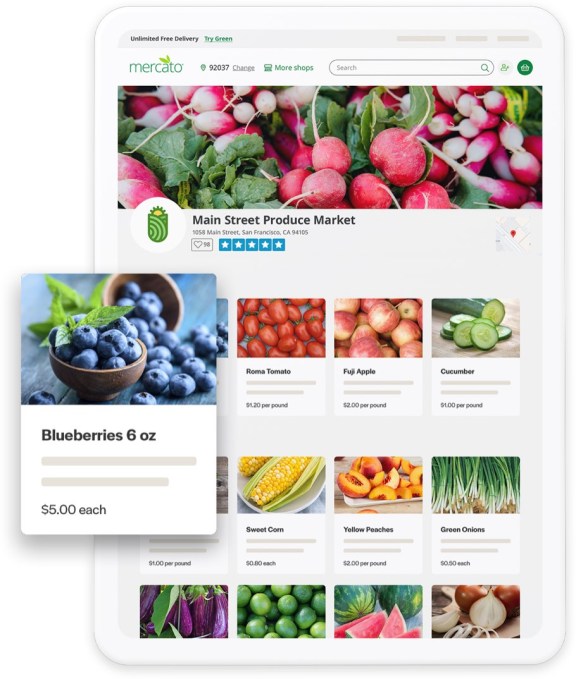

The result was Mercato, a platform-as-a-service that makes it easier for smaller grocers and specialty food shops to go online to offer their inventory for pickup or delivery, without having to partner with a grocery delivery service like Instacart, AmazonFresh or Shipt.

The solution today includes an e-commerce website and data analytics platform that helps stores understand what their customers are looking for, where customers are located, how to price their products, and other insights that help them to better run their store. And Mercato is now working on adding on a supply platform to help the stores buy inventory through their system, Brannigan notes.

“Basically, the vision of it is to give them the tech, the systems, and the platform they need to be successful in this day and age,” notes Brannigan.

He likens Mercato as a sort of “Shopify for groceries,” as it gives stores their own page on Mercato where they can reach customers. When the customer visits Mercato on the web or via its app, they can enter in their zip code to see which local stores offer online shopping. Some stores simply redirect their existing websites to their Mercato page, as they can continue to offer other basic information, like address, hours, and other details about their stores on the Mercato-provided site, while gaining access to Mercato’s over 1 million customers.

However, merchants can also opt for a white-label solution that they can plug into their own website, which uses their own branding.

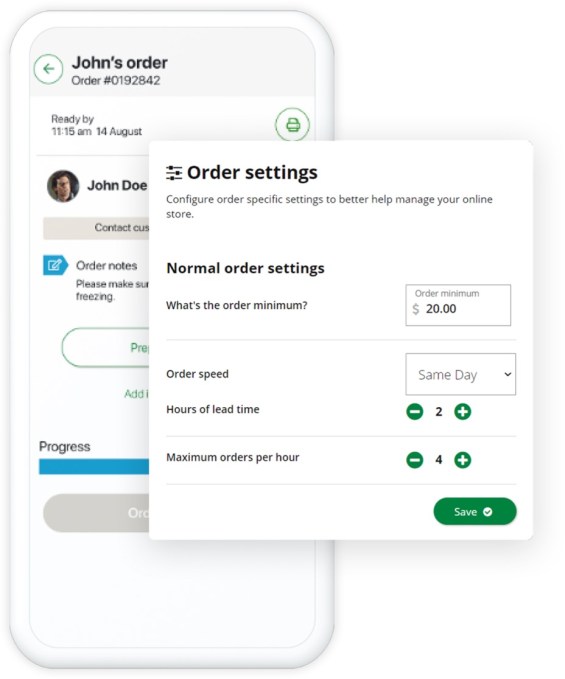

The stores can further customize the experience they want to offer customers, in terms of pickup and delivery, and the time frames for both they want to commit to. If they want to ease into online grocery, for example, they can start with next-day delivery services, then speed thing up to same-day when they’re ready. They can also set limits on how many time slots they offer per hour, based on staffing levels.

Image Credits: Mercato

Unlike Instacart and others which send shoppers to stores to fill the orders, Mercato allows the merchants themselves to maintain the customer relationship by handling the orders themselves, which they can receive via email, text or even robo-phone calls.

“They’re maintaining that relationship,” says Brannigan. “Usually, it’s a lot better if it’s somebody from the store [doing the shopping] because they might know the customer; they know the kind of product they’re looking for. And if they don’t have it, they know something else they can recommend — so they’re like a really efficient recommendation engine.”

“The big difference between an Instacart shopper and the worker in the store is that the worker in the store understands that somebody is trying to put a meal on the table, and certain items could be an important ingredient,” he notes. “For the shoppers at Instacart, it’s about a time clock: how quickly can they pick an order to make the most money.”

The company contracts with both national and regional couriers to handle the delivery portion, once orders are ready.

Mercato’s system was put to test during the pandemic, when demand for online grocery skyrocketed.

This is where Mercato’s ability to rapidly onboard merchants came in handy. The company says it can take stores online in just 24 hours, as it has built out a centralized product catalog of over a million items. It then connects with the store’s point-of-sale system, and uploads and matches the store’s products to their own database. This allows Mercato to map around 95% of the store’s products in a matter of minutes, with the last bit being added manually — which helps to build out Mercato’s catalog even further. Today, Mercato can integrate with virtually all point-of-sale (POS) solutions in the grocery market, which is more than 30 different systems.

As customers shop, Mercato’s system uses machine learning to help determine if a product is likely in stock by examining movement data.

“One of the challenges in grocery is that most stores actually don’t know how many quantities they have in stock of a product,” explains Brannigan. “So we launch a store, we integrate with the POS. And with the POS we can see how quickly a product is moving in-store and online. Based on movement, we can calculate what is in stock.”

This system, he says, continues to get smarter over time, too.

“We’re certainly three to five years ahead, and we’re not going back,” says Brannigan of the COVID impacts to the online grocery business. “It’s very plentiful now in many places, in terms of e-commerce offerings. And the nature of retail businesses is competitive. So if 1% of people are online, it might not drive other people. But if you have 15% of stores online, then other stores have to get online or they won’t be able to compete,” he notes.

Mercato generates revenue both from its consumer-facing membership program, with plans that range from $96/year – $228/year, depending on distance, and from the merchants themselves, who pay a single digit percentage transaction fee on orders — a lower percentage than what restaurant delivery companies charge.

The company has now scaled its service to over 1,000 merchants across 45 U.S. states, including big cities like New York, Chicago, L.A. D.C., Boston, Philadelphia, and others.

With the additional funding, Mercato aims to expand its remotely distributed team of now 80 employees, as well as its data analytics platform, which will help merchants make better decisions that impact their business. It also plans to refresh the consumer subscription to add more benefits and perks that make it more compelling.

Mercato declined to share its valuation or revenue, but as of the start of the pandemic last year, the company had said it was reaching a billion in sales and a $700 million run rate.